On October 25, 2023, videos poured out in Al Saraya, Gaza, that displayed a large cloud of smoke drifting into the skies, as a result of an Israeli airstrike. Bomb clouds are architecture in gaseous form: they consist of many aspects of what was once a building–cement, concrete, metal, wood, and more. They occupy the air that we breathe across different scales and durations.

Screengrab from reporter Younis Tirawi’s status, showing bomb clouds over Al Saraya, following intense Israeli bombings in Gaza City. October 25, 2023. Posted by Younis Tirawi on X.

This incident is one of many strikes that have occurred in the ongoing and brutal military bombardment of Gaza. The Israeli Occupation Forces’ (IOF) repeated strikes and attacks have significantly impacted the physical structure and organization of spaces in urban or rural areas across the Gaza Strip. During the IOF’s attacks, the morphology of space is significantly impacted as buildings are destroyed, infrastructure is damaged, and homes are demolished.

At the moment a strike occurs, it is important to find out when and where it happened. When locations are not immediately clear, identifying landmarks or distinctive topographical features in the cloud’s vicinity can aid in research. Matching the cloud’s location with known geographical aspects can help establish the precise location.

Airbus satellite image capturing the view towards the smoke clouds over Al Saraya, Gaza, at coordinates [31.514642334434214, 34.450994651238744]. Image courtesy of Airbus.

By combining the physical characteristics of the cloud with geospatial analysis, satellite imagery, and principles from a tool called Cloud Studies, investigators can build a comprehensive understanding of the incident’s location. This interdisciplinary approach, incorporating both Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) and forensic research, enhances the accuracy and reliability of the geolocation process. This technology can be used to bring forth high-grade documentation and evidence of past and current attacks on Gaza and the West Bank, and presents the Palestinian cause with a new dimension to resist Israeli occupation, opening the doors for new ways of accountability.

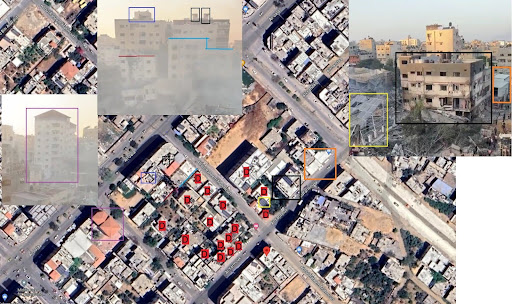

Airbus Satellite Imagery Detailing the Impact Site at [31.521543156653667, 34.460699873187835], Al Saraya, Gaza. Image courtesy of Airbus.

Annotated close-up view of buildings in Al Saraya, Gaza, showing the precise location of the impact. Image Courtesy of Airbus.

Photo documentation as an act of resistance

Palestinian resistance to colonization and the Israeli narrative that has long been supported by the United States and the European Union remains strong. It takes many different forms, one of which being Palestinians putting their lives at risk by grabbing their phones to take images and videos of Israeli settler colonial violence. Although it may be considered a trivial act, the documentation of violent instances can prove to be revolutionary. This type of resistance—a grassroots approach centered around “experience” and “memorization” rather than high politics, decision-makers, or top-down approaches—can challenge hegemonic discourses and colonial methodologies used by Israeli and Western-dominated information spaces that unconditionally support the Israeli government.

Satellite imagery has repeatedly proven to be a powerful instrument to hold oppressive regimes accountable and establish verifiable facts in places which would otherwise be difficult or dangerous to report on. Yet, in the case of Palestine, the quality of imagery provided by services such as Google has been abysmally poor and outdated. This was a result of a U.S. law called the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA). This law, introduced largely because of Israeli security concerns, blurred out satellite images of the occupied West Bank and Gaza to the point where the image resolution was of such low quality, one cannot even make out the shapes of cars on the images. On June 25, 2020, after two years of pressure from academics and civil society, the KBA was reformed, but Google refused to update its imagery. As such, the KBA is an indicator of how Israel controls what Palestinians can see and obscures their view as the quality remains degraded.

Additionally, Western social media platforms such as Facebook have been complicit with the Israeli colonial occupation by suppressing posts shared online by Palestinians and other Arabic-language posts far more than posts written in Hebrew. As Nadim Nashif and Marwa Fatafta, Al Shabaka policy analysts, pointed out: “Facebook’s confidential rules for moderating content related to violence, hate speech, terrorism, and racism, expose it’s pro-Israel bias.” Zionists, as shown in slides from Facebook’s moderation manuals, are a “globally protected group” amongst foreigners and homeless people, meaning that content attacking or criticizing them in a certain manner can be removed.

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT)

Part of confronting this integral part of Israel’s settler-colonial control is collecting all the pieces of footage that Palestinians share on the internet and archiving them with further details — such as the exact location, time, and date of the event. This data is also plotted on a map to serve as a database. This is called open source intelligence (OSINT), a methodology that “anybody can use.” It brings power back to ordinary citizens, such as myself, who care and show solidarity with subjects that are of public interest, such as the Palestinian cause.

Accurate geolocation of incidents in Occupied Palestine, documented and verified using Atlos, an Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) Platform. Image Courtesy of Atlos.

OSINT is akin to the process of building a bird’s nest, assembling disparate materials gathered from the surroundings. It applies archaeologists’ methodology in their quest for knowledge—constantly questioning and amassing a wealth of evidence. It involves the meticulous collection of footage, followed by a visual scrutiny of video clips and images from an event, culminating in the formulation of hypotheses. This rigorous pursuit of truth underscores the unwavering commitment of open source data scientists to document human rights violations and war crimes in the occupied Palestinian territories.

Comparing visual elements depicted in a video captured by an eyewitness and corroborating with corresponding details in satellite imagery and available tools at our disposal allows us to employ geolocation techniques to pinpoint an event’s precise location. This process, in turn, unveils a multitude of inquiries: What is the nature of the event? What specific details do we observe? When did it occur? Are there casualties? What types of violence have been deployed? The answers to these questions constitute a crucial step in investigative work.

A practical example: Raids through the eyes of OSINT

To get a better understanding of how OSINT works, take for instance this video taken during one of the raids by the IOF in June 2023 in the West Bank city of Jenin. In this video, Palestinian journalists were seen laying on the ground and covering themselves as Israeli snipers shot at them. There aren’t any distinct landmarks such as a mosque or residential building in the footage. But in the beginning of the video, one can note an electric type of construction with antennas on top of the hills.

Screengrab from a Palestinian Eve Network video, showing Israeli snipers and journalists in Jenin on June 19, 2023. The antennas highlighted in the image helped pinpoint the location. Al-Jabryat neighborhood. Jenin, West Bank, Palestine. Posted by Palestinian Eve Network on X.

As background, Palestine, grappling with the relentless transformation of its landscape due to ongoing settler colonialism, boasts a remarkable topographical diversity. It spans from approximately 440 meters below sea level along the shores of the Dead Sea to elevations of around 1000 meters in the towering peaks of the northern West Bank. For instance, Jenin, a symbol of Palestinian resilience in the face of frequent Israeli incursions, is nestled at the base of the rugged hills of the northernmost West Bank (Jabal Nablus), overlooking the southern expanse of Marj Ibn Amer.

By looking around the hills (S/W) of Jenin Refugee Camp, I moved through the al Jabryat neighborhood and managed to spot this place that resembled a tower shaped object on the satellite imagery, which looked a lot like the antenna seen in the video shared on social media. As previously done with the frame, we make an annotation and start to look further.

Satellite image annotations reveal the location of a construction site with antennas in the Al-Jabryat neighborhood. Jenin, West Bank, Palestine. [32.45704652824203, 35.28295252425132].

We use Mapillary to take a closer look at the structure that was located on top of the hilltop. Mapillary is a crowd-sourced platform that collects street-level imagery from dashboard and roof-mounted cameras. While it doesn’t cover all of the West Bank, it does have a lot of coverage in many Palestinian villages and cities.

Locating the structure with antennas using street-level imagery collected from dashboards and roof-mounted cameras using crowd-sourced platform Mapillary. Image Courtesy of Mapillary.

Having successfully located the structure with the antennas atop the mountain, the next step is to descend from that very mountain towards the refugee camp. Given the absence of street view capabilities in this area, we opt to employ a tool called PeakVisor. Originally designed for outdoor enthusiasts and hikers to effortlessly identify mountains with a few clicks on their phones, we adapt its use for open source investigative purposes. In our context, it serves as a valuable resource to pinpoint locations where state violence has encroached upon the freedom of the press, as exemplified in Jenin.

Using PeakVisor to match the surrounding hills, the location where the Palestinian journalists were shot was identified. [32.462604405586426, 35.28869756340405]. Image courtesy of PeakVisor.

The gathered data is subsequently archived within Atlos, the open source platform designed for visual investigations. and dedicated to collaborative efforts in cataloging and geolocating eyewitness media. To date, we have effectively documented 661 incidents in occupied Palestine, encompassing a range of violations by Israeli forces including home demolitions, acts of settler violence, military incursions, and obstruction of medical teams and facilities.

A screenshot from Atlos’s collaborative dashboard detailing precise geolocation data of an incident from July 3, 2023, near Jenin, where the IOF fired a rocket launcher at a residential building. Image courtesy of Chris Osiek on Atlos.

Collaborations with activists on the ground

While our efforts have garnered attention, including collaborations with more Western news outlets like The Washington Post and CNN, the true measure of fulfillment lies in empowering Palestinians to use these practices of counter-mapping to their own advantage. Last year, I began to collaborate with the Forensic Architecture Investigation Unit at Al-Haq, a Palestinian human rights organization, to explore possibilities for using open source data and evidence to bolster legal accountability and enhance public advocacy.

While research rooted in open sources provides valuable insights, its limitations become evident when it comes to eyewitness testimony, access to local communities and places for assessment, and gathering on-the-ground evidence. But the remarkable Palestinian team at Al-Haq complements our efforts with traditional field research. They enhance the grassroots approach by engaging in interviews, capturing on-site photographs, and conducting in-person assessments. This fusion of traditional research methods such as gathering first-hand accounts on-the-ground and modern methods such as open source data represents a harmonious convergence of the best of both worlds, bolstering the amount of data and credibility.

So far, we have provided Al-Haq with geolocation data for an interactive urban narrative that studies and analyzes two deadly Israeli raids on the Palestinian cities of Jenin and Nablus in January and February 2023. The data demonstrated that there was a recurring pattern in undercover IOF operatives dressed in civilian attire for incursions into Palestinian urban areas and refugee camps. Our research uncovered a disturbing practice wherein IOF personnel reconfigure the familial structure of targeted residences, effectively converting them into military hideouts, thus endangering the lives of innocent families within. Subsequently, the IOF surrounded the besieged structure, deploying anti-structure missiles that inflicted severe damage on civilian infrastructure.

Furthermore, the comprehensive inquiry illustrates the IOF’s adoption of a strategy referred to as the ‘pressure cooker approach.’ This extrajudicial method entails a gradual intensification of force applied to a specific location, with the aim of coercing any occupants to surrender. In cases of non-compliance, the IOF may resort to the demolition of the structure, tragically resulting in the loss of lives for all those within.

Our examination found a deliberate arrangement of Israeli military vehicles strategically designed to impede all entry and exit points within the targeted area. Simultaneously, additional military vehicles are strategically deployed to quell any protests. This calculated placement of Israeli military vehicles effectively establishes a barricade, severely restricting both ingress and egress from the attacked zone.

Counter-mapping to reclaim Palestinian narratives

Zionist cartographers, geographers, urban planners, and military strategists have historically harnessed the power of maps and technology to further their objectives. In collaboration with Palestinian researchers, we have initiated a compelling counter-narrative, challenging these tactics through innovative forms of resistance.

Ariel Sharon and Ehud Olmert, both former Israeli presidents, leveraged maps as tools of policy and strategy for Israeli colonial politics. Sharon, known for his involvement in settlement expansion, used maps to plan and expand Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Olmert, on the other hand, employed maps during his tenure to outline proposals for the reconfiguration of borders and the separation barrier.

Counter-mapping allows Palestinians to reclaim their narratives and assert their presence and rights in the face of occupation. It helps communities to tell their own stories and provide alternative perspectives to official Israeli narratives via new tools. This process is crucial for making the Palestinian cause more accessible to a global audience as increased awareness can lead to greater international solidarity and support.

The visualization of the impact of Israeli violence also serves as further evidence to international accountability mechanisms prosecuting and/or investigating war crimes and human rights abuses, including the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice.

Hand in hand with the courageous people of Palestine, we stand in resistance against the dominant discourse, championing an alternative vision of liberation.

Chris Osieck is a former digital marketing professional who turned into a self-taught Open Source Researcher. He uses his analytical and result-driven mindset to document human rights abuses and war crimes by fusing innovative open source investigative methodologies with trusted indigenous experts.

-

Chris OsieckFebruary 18, 2024